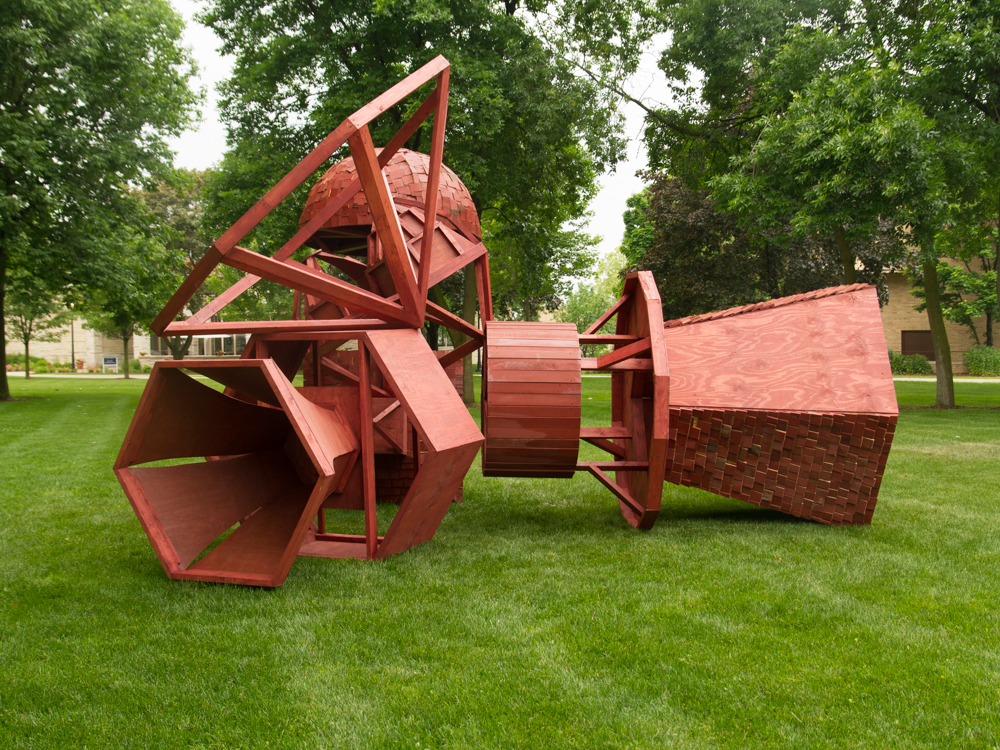

Spring Loaded is a temporary public installation created in collaboration with Carroll University faculty, staff, students, alumni, and community members including artists, high school students, and retirees. The site-specific project was sponsored by the Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund. It draws on Waukesha’s local history and material culture from the late 19th century Great Spring Era. The artwork was produced in a collective manner, following research and interviews with historians and water resource specialists. Designed and built over a 3-week period in early June 2015, the sculpture recreates and remixes the forms of wooden and stone water pavilions.

These structures were built to serve visitors to the town, as it underwent a boom in tourism from people claiming miraculous cures to kidney diseases, constipation and other illnesses. Many were remodelled and repainted over time, as each Spring House and later, bottling plants, sought to attract a new clientèle. Rather than being preserved or reconstituted for future generation, almost all of the actual gazebo-like follies disappeared as the boom turned to bust by the early 20th century. Nevertheless, photographs and first-hand accounts document their appearances and uses.

During the first week of the project, KM Perform Charter School students and I met with curators at the Waukesha County museum and documented archival photographs and stereoscopic cards from the Spring Era through drawings and photography. We also visited the interior of the octogonal Silurian Spring House, met with local historian John Schoenknecht, and interviewed local Avalon retirement home residents about their memories of water resource use. Students created models in cardboard that recreated the radial symmetry of the original Springs Era Pavilions.

Together, we combined the individual forms in different ways to come up with an artwork inspired by these symbols of decadence, prosperity, and local pride. During the following weeks, I created technical drawings and we worked with local artist volunteers to scale up the model using timber frame construction to support cladding cut from red barnwood, re-used from an existing construction project, at the Carroll University Field Station. The finished piece was installed on the campus’ main lawn during the final week of the project.

The Spring Era ended as a result of both cultural and physical transformations to the local landscape. As automobiles became more prevalent, visitors abandoned train travel as a means to get to their holiday destinations, and federal guidelines limited the Springs’ ability to advertise their supposed “curative properties” due to a lack of scientific evidence. Commercial and residential development, including paved surfaces and the pumping of water from local quarries, blocked infiltration of rainwater into the soil, and certain springs became contaminated with bacteria from outhouses and storm water draining from nearby industries and farms.

As the town grew, it also dug deeper and deeper wells, leading to a high concentration of radium in the local drinking water. This ironic situation exemplifies the tragedy of the commons; rather than accessing limited water resources in a sustainable manner, users assumed that the local springs would last forever. These issues are particularly relevant in light of ongoing debates regarding water use in the Western United States and the boom and bust cycles of natural resource use more generally, within energy production.

Rather than romanticising the past, Spring Loaded ties symbols of the Great Springs Era to issues of water use and local identity. It seeks to increase awareness of the this period in local history, but also of the physical and geological dimensions to the local landscape. The sculpture prompts viewers to ask questions about the origin of the fanciful and whimsical forms presented and about water use and conservation, past and present.